William Muriel (Ely,1794 - Ely,1876)

R.N.Commander and Surgeon

By Simon Dewes

WILLIAM MURIEL was the fourth son of my great-great-grandfather, Robert Muriel, D.L., J.P and Surgeon of Ely, who was thrice married, fathered a family of 16, of whom no less than 15 survived and, of that 15, 10 lived to be 70 or more.

When William was seven years old - and his father's family numbered 11- he was sent as a boarder, to some kind of school in Yorkshire, prototype of the Dotheboys Hall of which Charles Dickens was to write. Two years later, at his own request, he was brought home to Ely where, until he was 11, he attended what is now The King's School, where he was taught by the Reverend George Miller.

Mr. Miller's lessons - whatever the subject were coloured by an intense patriotism and they generally ended by vivid accounts of the Battles of the Nile and of Copenhagen. The British Navy, Mr. Miller told his enthralled classes, was, undoubtedly, the agent by which the might of France and of Napoleon would be crushed. And the British Navy-according to Mr. Miller-relied largely on East Anglians, notably Admirals Sir Hyde Parker and Sir Peter Parker of Long Melford, and Horatio Nelson, the son of a Norfolk Rector.

It is little wonder that, at the age of 11, William Muriel volunteered for the Navy and was appointed midshipman on H.M.S. Hero. This was in March 1805. In the following September he transferred to Bellerophon. On 21st October he played his small part in the Battle of Trafalgar, where his hero, Nelson, was killed and William received a medal.

In 1812 William was gazetted lieutenant and took command of St. Joseph, blockading Cadiz and the Straits of Gibraltar, until he was ordered to attack the island of Ponza (Pontia) 70 miles north west of Naples. The attack on the island lasted less than a week, when the Italian-Spanish garrison drew off under heavy fire.

The little English fleet anchored in the harbour; and William Muriel took over command of the island, where he remained until the end of the war after the Battle of Waterloo. He and his brother officers appear to have behaved in a fairly civilised fashion as occupying troops. They took turns in shore leave. They were all very young and, years later, the most exciting thing that William remembered about his time there was regularly bathing in the bath that had been built by Pontius Pilate after his removal from the Holy Land.

The Bonapartes had, however, been forced to leave all their treasure behind them and, on William's return to England in 1816, a good many wagon loads of this were despatched to Ely where it remained until 1906 when, under the terms of an extraordinary will-the subject of much litigation-left by William's niece (my great aunt) Eliza, it was dispersed all over the country.

The war was over and William proceeded to Chatham, where he had command on the Guardship Bulwark. For the rest of his naval career - with only one glittering interval - he was stationed at Chatham; and, in his own words, 'for four years I did nothing but dance with the ladies'.

As his final naval task, in June 1820, Captain Muriel was given command of the flotilla that sailed to Dunkirk to escort the future King William IV and Queen Adelaide to England.

It was the most glittering occasion of his life. His little fleet, decked over all, came into Dunkirk harbour where, for nearly three weeks, there was lavish entertainment. For 10 days Muriel stayed on the Duke's yacht where his four years of dancing at Chatham served him well. For a further week the Royal Party cruised in the Admiral's yacht which had been lent to Muriel. It was all very light-hearted.

In the first week in July, flags flying, bands playing, people cheering and guns firing in salute, the flotilla sailed into Tilbury, and Muriel's naval career was at an end.

Six' weeks later he retired on half-pay and entered Guy's Hospital as a student, He was 26 and he had 56 more years to live,

To some members of his family it seemed impossible that, after his active and exciting young manhood, he should willingly accept the humdrum existence of a surgeon-apothecary. But for William Muriel there had never been any other choice. From the age of 11, when he had first seen the carnage of battle, through the years afloat when men had died wastefully and unnecessarily from fever and disease spread by dirt and ill-feeding, he had been determined that, if he survived, he would save life rather than destroy it.

Nevertheless, as he remarked in later life, during his time at Guy's he saw more bloodshed and butchery than he had ever seen in battle, This was a gross exaggeration but, in 1824, there were no anaesthetics (ether was first used in about 1847 and chloroform later than that): and operations (99 per cent of them amputations) were performed either when the patient was fully conscious or had been stupefied by alcohol.

In 1827 Muriel qualified and his father suggested he join his younger brother, John, who was already in practice in Ely. But William had other ideas and purchased a practice at Wickham Market in Suffolk, buying, at the same time, a house that still stands on the Market Hill.

And now his life, of which more than 40 years was to be spent in Wickham Market, became divided into two quite distinct compartments, which never seem to have overlapped. All day - save one day a week - he worked assiduously at his practice. His 'day off' and his evenings he spent in the company of those who might have been his brother officers in the Service. He hunted. He shot. He fished. He had his boat at Orford. He dined out frequently and he gave dinners and he was a regular attendant at most of the Subscription Balls all over the county.

But the whole meaning and purpose of his life now lay in the healing of disease and the assuagement of pain; and it is on record that, on occasions, he could be extremely rude to his wealthier patients when they summoned him from attending the seriously sick to attend their own minor ailments. Thus, to the Hon. Mrs. North of Glemham Hall, who had sent her groom to bid him come immediately, he sent a brusque reply that she should drink peppermint cordial instead of brandy and water; he told Mr. Archdeckne to layoff port altogether and take horseback exercise.

In spite of this, his friendship with these people remained unbroken.

My own father, who knew him well, told me that William's most constant voluntary call was at the Plomesgate Union Workhouse which was built in Wickham Market in 1836. The previous workhouse had been at Melton, but, in 1827, the building there was taken over as the Suffolk Pauper Lunatic Asylum and, for the 10 years following, vagrants had no place of rest between Ipswich and Saxmundham. This, following decades of war, was a desperate hardship and the roads were crowded with maimed and un employed ex-servicemen.

In the 20 years from 1830 to 1850 it was necessary to build no less than 10 new workhouses in Suffolk; and that at Wickham Market had, soon after its erection, a permanent population of pauper residents of at least 300. There was also a floating population of vagrants, averaging 50 a night. Under the existing laws these vagrants might only stay in one workhouse for one night. After that, unless a doctor certified them as unfit, they must move on elsewhere. This law was rigorously imposed, for the vagrants were a charge on the parish rates and the thing to do was to pass them on as quickly as possible.

It was the sight of one-legged men - the heroes of Trafalgar and Waterloo - struggling on the dozen miles to the next workhouse at Eye or Ipswich that spurred Dr. Muriel to action, for no medical examination was yet automatically given at these places. And so, for the next 40 years, three times a week and sometimes more often, Dr. Muriel called in at the workhouse at 7 a.m. and, when he could, ordered those in want and those suffering to be detained. I am told, too, that he frequently handed over small coins, though this was a risky business, for a vagrant caught with any money had it immediately confiscated and was automatically committed to prison.

When he was just over 40 William Muriel married Catherine Alexander, a sister of the Bishop of Derry, whose wife, Cecile, became famous as the author of many famous hymns. Catherine bore him three children but she and they all pre-deceased him: and, in 1870, Dr. Muriel, after 40 years of doing good, left Wickham Market and returned to Ely to live with his eldest sister, Mary.

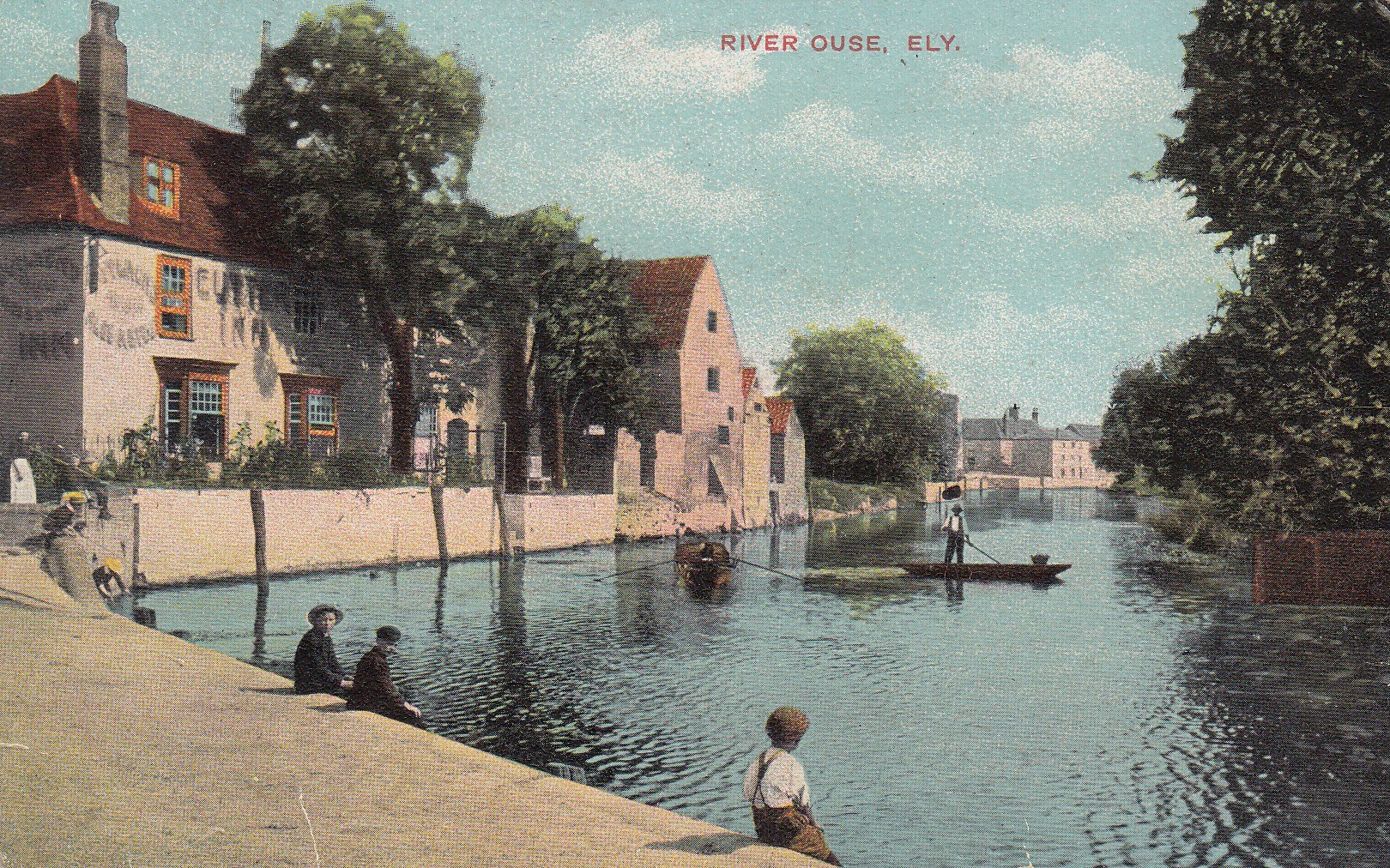

There, in a house looking over the Market Place, cluttered up by the Queen of Italy's treasure which he had helped to plunder, and visited by his innumerable relations, he passed the last six years of his life.

When, in 1876, he died, The Times recorded: 'Another of our ancient sea-heroes has passed from among us, ripe in years, rich in honour, respected by all. His memory will long be revered.

But perhaps his best memorial lies in the small coins that he surreptitiously pressed into the hands of the crippled heroes who may, some of them, have once been his shipmates.

The Ipswich Journal,14th November 1876:

Death of a Naval Veteran. The Late Captain William Muriel, R.N.~Another of our ancient sea heroes has ceased from amongst us, ripe in years, rich in honour, and respected by everyone. We append a brief narrative of some of the most important episodes of his public life, kindly supplied by a friend. William Muriel, third son of the late Mr. Robert Muriel, of Ely, surgeon, was born at Ely on the 7th of May, 1794. At the age of 11 he entered the Royal Navy, as midshipman on board His Majesty's ship, Hero, in the year 1805, a short time before the battle of Trafalgar, at which time a medal was given to him. Two years afterwards he was transferred to His Majesty's ship, Dragon, whence, after two years' active service, he proceeded to the Baltic, on board the; Bellerophon, and was then commander of the most important boat action of that period, for which he was awarded another medal. On his return from the Baltic, in 1809, he was appointed to the Blossom, and thereafter was transferred to the St. Joseph, and was actively engaged in the war between France and Italy, and was gazetted Lieutenant in 1812. Two years afterwards he was successful in an attack upon the Island of Ponza, off the coast of Naples, which he captured. In 1817 he was appointed to the Bulwark guard ship. In the year 1820 he had the distinguished honour of being sent to Dunkirk to bring home to England their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Clarence, afterwards William IV. and Queen Adelaide. The following year he retired on half pay as captain, and devoted himself to the medical profession, in which he obtained considerable distinction as a surgeon. Holding his diploma of Guy's Hospital, he practised for 40 years at Wickham Market, Suffolk, until the death of his wife and children, when he left, and returned to end his days among his relations and friends in his native city of Ely. There on Wednesday he died in peaceful resignation, in the 82nd year of his age. His memory will long be revered as a notable member of a most estimable family, which, we regret to know, is one by one fading away from among us.”